Contributors: Angie Winter, Ph.D. and Rachel Bryars

Think through your typical work week – what are the moments when you feel you need to be “on” and perform well?

Most of us have recurring work moments that can be thought of as “performances” — such as leading a presentation, hosting a meeting, submitting a proposal, or even having a difficult conversation.

Often, these performances can create increased stress, muscle tension, and anxiety. That increased physiological activation in our bodies, along with the typical cognitive increase from over-thinking, plus the emotional arousal of worry, dread, or fear, can negatively impact our performance. This can occur even if we aren’t entirely aware of what is happening or why.

Is there anything we can do cognitively, emotionally, and physiologically to perform at our best when we find ourselves in this position? What steps can we take to ensure we don’t self-sabotage when we need to perform?

We need emotions to get in the zone of optimal functioning

Most of us have heard the phrase “get in the zone.” What does that mean and is it an attainable goal? While athletes have been casually using the phrase for many decades, there is a theoretical approach from the field of Sport Psychology called “The Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning Model” that can help us understand where to be and how to get there.

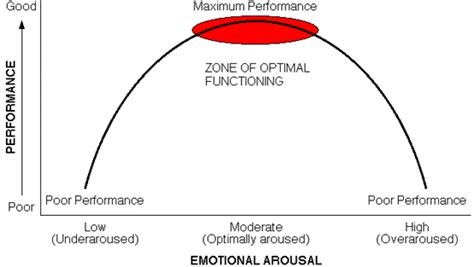

Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning Model,2,3 Yuri Hanin

This model, from psychologist Yuri Hanin’s work,2 depicts a zone of optimal functioning that occurs at a particular level of emotional arousal. The model suggests that as our emotional arousal builds, the quality of our performance also builds, but only to a certain point. Hanin calls this point at which performance is maximized the “Zone of Optimal Functioning.”1

However, as our emotional activation continues to build, it eventually works against us and the quality of our performance drops.1 Our optimal level of emotional activation varies by individual and task.1 For example, reading a book generally requires less emotional arousal or interest than it takes to lead a client meeting.

What emotions do you need to perform well?

Therefore, it is important to consider our specific tasks and think through how much emotional arousal is necessary to perform at our optimal level.2,3

To do so, think about the task at hand and ask yourself: What emotions, and at what level, are necessary for me to perform at my best? The emotions that come to mind are called your Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF) indicators.

These indicators are reflected both in our physiology and in our state of mind. When we perform our best, we are typically calm, relaxed, a little excited, and focused on the task at hand; our bodies are not tense, our heart rate is normal, and we are not dwelling on past or future thoughts.2,3

Since our Zone of Optimal Functioning is relatively narrow, we often may find ourselves either too emotionally activated or not activated enough. With too little arousal our bodies are not properly activated for the task at hand — blood flow is restricted, cognitive responses are slower, and movements are slow and without direct effort.2,3

On the other hand, too much emotional arousal overly excites the body – we experience increased heart rate, feelings of anxiety, and overwhelming thoughts.2,3

Optimal functioning doesn’t just happen

So, should we try to get ourselves into the “zone” or build strategies for all the moments we’re not in the zone? Getting into our zone of optimal functioning won’t just happen automatically, especially when we have an important performance. Reality is that we are often under or over activated and we have to perform anyway.

Thankfully, we have two great options when we realize we are not in our zone of optimal functioning.

- We can work to get ourselves closer to our optimal state. If we are under-activated, we can increase our heart rate by standing up, moving around, or even taking some quick breaths. If we are overactivated, taking some slow, deep breaths can get us closer to our optimal state.

- We can utilize three skills and strategies to manage ourselves in the moment, wherever we are.

- Deliberate breathing is a great skill to bring ourselves back to the present moment and regain control.

- Reframing is another tool that can cognitively help us to change our mindset from dwelling on negatives, failures, and mistakes to seeing how our experiences bring learning and growth. This requires intentionally shifting your thoughts to something more positive and productive. For example, after a poor night of sleep I could be thinking all day about how tired I am or reframe my thoughts to “I’ve done some great work in the past while tired, I can do it again today.”

- Growing and maintaining a growth mindset allows us to focus on pursuing challenges and learning from our mistakes. This requires we move away from getting stuck in the opposite – a fixed mindset – in which we tell ourselves that no matter how much effort we put forth, we cannot change.

Self-awareness is the key component to using this model to our advantage, especially when we find ourselves outside of our “zone.”

For your next big meeting, presentation, or client engagement, check in with yourself. If you are feeling anxious or unmotivated, deep-breathing exercises, productive reframing of your thoughts, and approaching your tasks with a growth mindset are all proven methods that will help you focus on bringing your best self to your performance.

Ready to take your performance to a higher level?

HigherEchelon delivers evidence-based human capital services solutions including assessments, high performance solutions, executive coaching and training programs to take you and your team to the next level. Get in touch today for a first conversation: Call us at 256-724-8843 or fill out this form to get started.

Read our whitepaper about our approach to developing high performance in portfolio companies

RESOURCES

1) Kamata, A., Tenenbaum, G. & Hanin, Y. (2002). Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF): A Probabilistic Estimation. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 24. 189-208. 10.1123/jsep.24.2.189.

2) Hanin, Y. L. (1997). Emotions and athletic performance: Individual zones of optimal functioning model. European Yearbook of Sport Psychology, 1, 29-72.

3) Hanin, Y. L. (2000). Emotions in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Shrujal Joshi contributed to this article